I was recently asked by Frank from the Upgrade YouTube Channel to collaborate on a video on the Whittier Blvd Arch. This got me thinking about what other history could be found along Whittier Blvd, so I put together a little history tour. In the words of Thee Midniters, “Let’s Take a Trip Down Whittier Blvd!”

Our first stop brings us to the iconic Whittier Blvd arch. Which can trace its history back to the mid 1980s and is the result of the hard work of the Whittier Boulevard Merchants Association and the community.

Whittier Blvd had been a major shopping district for the area’s Latino population for many years, but the street fell into decline following a riot that erupted during an anti-Vietnam War demonstration in 1970 where scores of people were injured, 3 were killed, and dozens of stores sere looted and burned, Soon after, the Blvd fell into decline, faded signs, cracked sidewalks, litter, and graffitied walls became the norm, but the Merchants Association was determined to revitalize Whittier Blvd.

The Merchants began to formulate a plan in 1978 and were able to obtain government help in 1982, however, financial conflicts between state and county officials caused delays.

Finally in 1984, they secured $1.8 million from the state for road work, with the county providing an additional $1.4 million and $3.1 million in community development grants for building and sidewalk improvements. Around $5 million in private funds from the merchants was used to refurbish their buildings.

The centerpiece of their redevelopment project was the iconic Whittier Blvd arch, named “El Arco,” it’s a 5-story, 14-ton steel arch that spans 65 feet and cost $280,000 to build. It was formally dedicated on Jan 18th, 1986.

El Arco has not only become an iconic landmark of East L.A., but also a symbol of Chicano culture; being forever associated with lowrider culture and embodying the community spirit of its residents and Merchants who that made it possible.

Our next stop brings us to the Latino Walk of Fame that runs along Whittier Blvd, there are over 250 slots cut into the sidewalk to hold red granite markers like the one below. However, if you take a stroll down Whittier Blvd you’ll only find a few names scattered throughout. Which is far from the vision that its planners had when they planned this landmark back in 1984.

After securing funding for the redevelopment of Whittier Blvd, one of the projects that emerged was the creation of the Latino Walk of Fame, to not only honor those that have made significant contributions to the Latino community, but to also draw visitors, much like the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Slots were cut into the sidewalks on the street in anticipation of sundials that would commemorate activists, celebrities, and hometown heroes. However, the Latino Walk Of Fame didn’t get its first plaque until 1997 when a granite sundial commemorating the establishment of the walk was installed in April of that year. This was followed by the first honoree, Cesar Chavez, getting his plaque in July. Hundreds of people attended the unveiling of the sundial honoring the labor leader and civil rights activist. The Latino Walk of Fame continued to add new honorees about once a year until 2008, with Edward Roybal, Richard Chavez, Jaime Escalante, Fernando Valenzuela, Romana Acosta Bañuelos, Maribel Guardia, Edward James Olmos, Antonio Aguilar, Jose Jose and Graciela Beltran being honored before the walk went dormant.

So what happened? Well, like most things it all comes down to money. A project like the Latino Walk of Fame requires funding to install new plaques and for its upkeep.

Each sundial comes with a price tag of around $10,000, which covers street closures, security provided by the Sheriff’s Department, and the sundial itself. When the walk was established, the Whittier Boulevard Merchants Association was receiving funding from the county for each ceremony, but the county’s finances took a major hit during the Great Recession and never fully bounced back and sponsorships from local businesses are nearly impossible as East L.A. struggles to rebound from the economic toll of the Pandemic.

Given the economic circumstances, it’s hard to say if there will ever be another inductee into the Latino Walk Of Fame, which is truly a shame, because the Walk of Fame was a source of pride for East L.A. residents and it had the potential to be an iconic landmark.

Our third and final stop brings us to the wall outside of the Sounds of Music Record Shop, where a simple black plaque marks the spot where over 50 years ago, one of the most prominent voices of the Chicano movement, Ruben Salazar, was killed under circumstances that remain shrouded in controversy to this day.

Ruben Salazar was born on March 3rd, 1928 in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico and raised in El Paso, Texas, where after graduating from high school, he served in the U.S. Army for 2 years and then graduated form Texas Western College with a degree in Journalism.

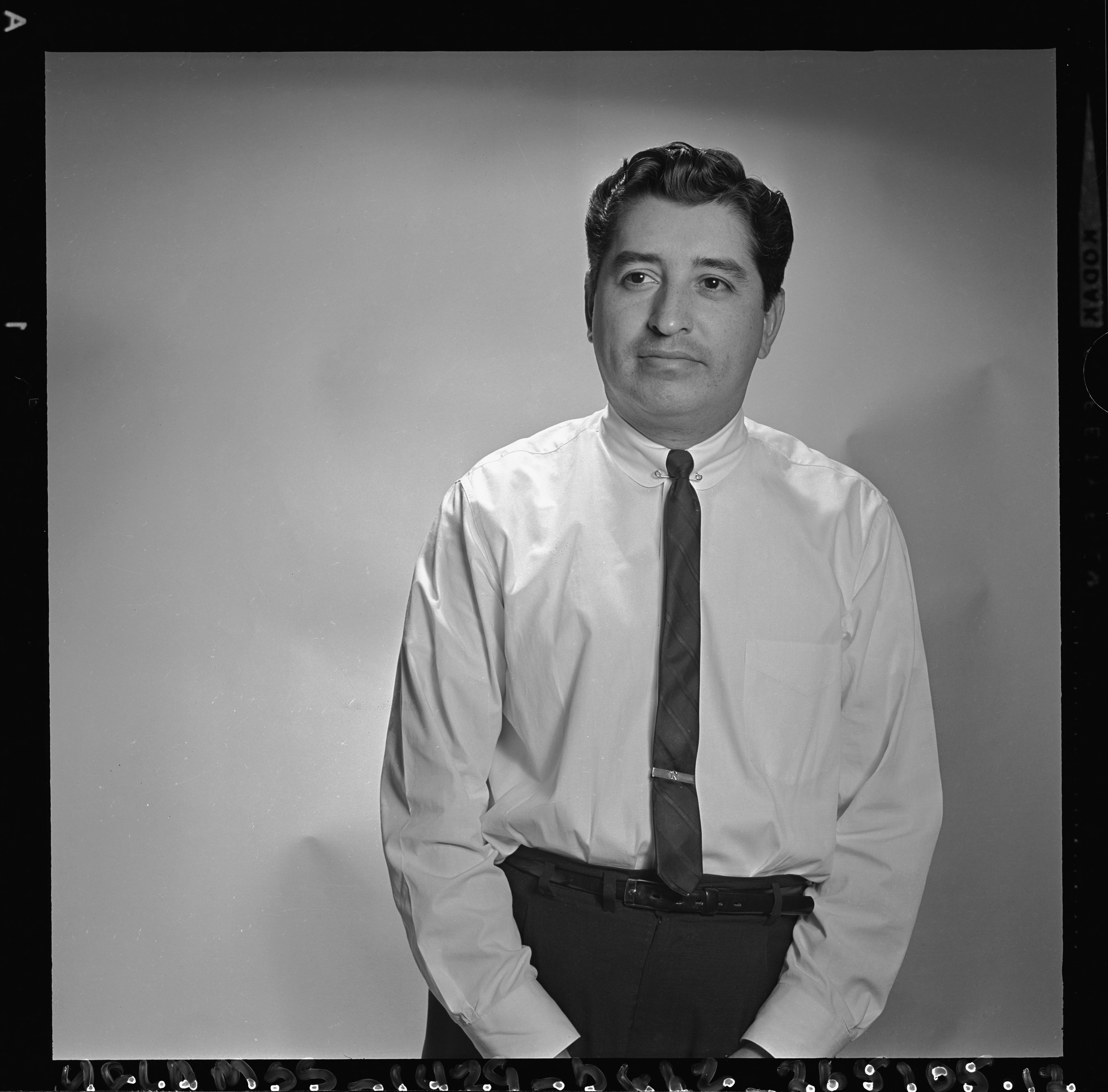

Photo Credit: UCLA Special Collections.

Salazar became an investigative journalist at the El Paso Herald-Post, where we he penned remarkable stories, including posing as a vagrant and getting himself arrested in order to expose the deplorable conditions inside the jail and traveling to Juarez to buy drugs from a notorious drug queenpin.

After his time at the Herald-Post, Salazar moved to California where he worked for The Santa Rosa Press-Democrat and the San Francisco News, before going on to work for the Los Angeles Times in 1959. There, his work focused on the economic and cultural issues affecting Mexican-Americans, particularly in education and employment, as well as the struggles of Braceros and farmworkers. His reporting raised awareness within the Mexican-American community about their political and economic marginalization.

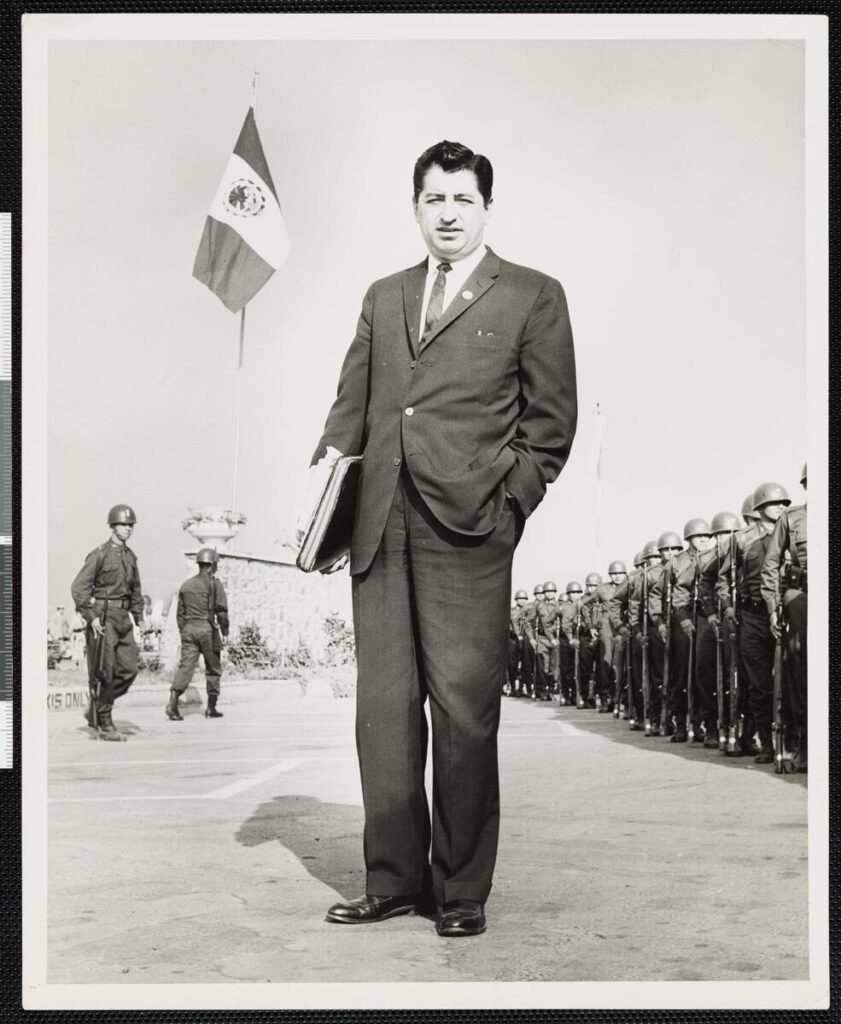

As his career progressed, Salazar was assigned to cover international conflicts, including the civil war in the Dominican Republic and the Vietnam War, before being assigned to be the Mexico City bureau chief for the Times in 1966, where he covered indigenous issues and the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre.

Photo Credit: From the Ruben Salazar papers, USC Libraries, Special Collections

Salazar returned to the US in 1968, where his work again focused on the Mexican-American community and the Chicano movement, primary focusing on East L.A., an area that was largely ignored by mainstream media except for coverage of crimes. He often criticized the local government’s treatment of Chicanos, especially the heavy handed tactics of the police.

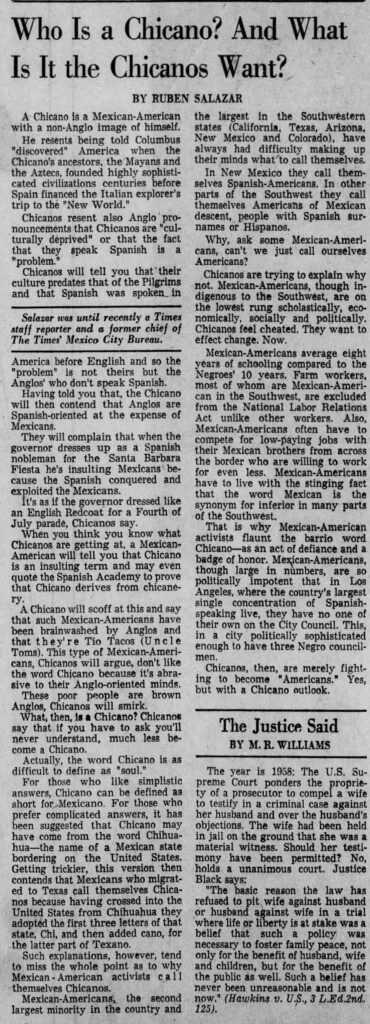

In February of 1970 he made his support of the Chicano movement clear in his Article, “Who is a Chicano? And What is it the Chicanos Want?” Salazar highlighted the evolving Chicano identity and the movement’s significance while expressing frustration over the lack of Mexican-American representation in Los Angeles politics.This activism led to surveillance by the FBI and the L.A.P.D.

Salazar would leave the L.A. Times in January of 1970, to become the news director for Spanish language TV station KMEX, but would continue to write columns on Chicano issues for the Times. At KMEX, he focused on key issues affecting the Chicano Movement, including the police killing of the Sanchez cousins, which sparked widespread protests, and the Chicano Moratorium, which eventually led to his death.

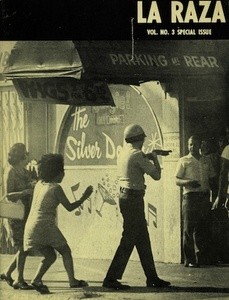

On Aug. 29th, 1970, Salazar was covering the National Chicano Moratorium March that had been organized to protest the Vietnam War and the disproportionate number of Latinos who served and were killed. More than 20,000 people marched from the East L.A. Civic Center to a rally at Laguna Park. The march and rally were peaceful, but after sheriff’s deputies responded to reports of theft at a nearby liquor store, they decided to clear the peaceful gathering by firing tear gas canisters and attacking protesters with batons, which led to panic and rioting.

Photo credit: UCLA Special Collections

Salazar and his crew left Laguna Park and worked their way east along Whittier Blvd, stopping at the Silver Dollar Cafe to use the restroom and grab a quick beer. Unbeknownst to the patrons inside, sheriff’s deputies were outside responding to a report of two armed men inside the bar, a report that later proved to be false.

Photo Credit: From the Ruben Salazar papers, USC Libraries, Special Collections

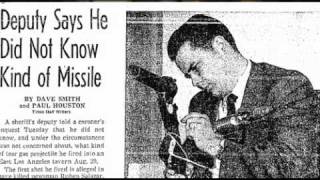

Salazar had just sat down when a sheriff’s deputy fired a tear gas projectile blindly into the bar through a curtain hanging in the doorway, hitting Salazar in the head and killing him instantly. The deputy had fired a 10-inch wall piercing torpedo-shaped missile that was designed to be used in barricade situations and not the rolling type gas canister that is typically used to disperse crowds. Despite firing a projectile that was not authorized for use in the type of situation in which Salazar was killed, no charges were filed against the deputy. Although a 1973 lawsuit awarded his family $700,000, the ruling did not suggest the sheriff’s department was guilty of misconduct.

The circumstances of his death have long been scrutinized, even after records of the shooting were made public in 2011 and no official wrongdoing was found, there are still those that believe that he was intentionally targeted that day.

Salazar’s death had a lasting impact, becoming a martyr of the Chicano Movement and role model for Latino journalism students. He was awarded the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award posthumously and numerous honors followed, including the renaming of Laguna Park to Ruben Salazar Park, scholarships in his name, and being featured on a U.S. postage stamp.

The Silver Dollar Cafe eventually closed and the store front went through many different tenants, but throughout the more than 50 years since Ruben Salazar’s death, this place has been become hallowed ground of the Chicano Movement, where one of its most prominent voices was silenced, but never forgotten.