In the spirit of the Halloween season, I decided to visit 3 spots across the Southland that are alleged to be haunted. It was quite the road trip–spanning 3 counties, but it was both informative and a bit spooky.

Our first stop is the Olivas Adobe in Ventura. This building dates back to 1847 and was once the home of the prosperous Olivas family and some say, a few of them, still remain.

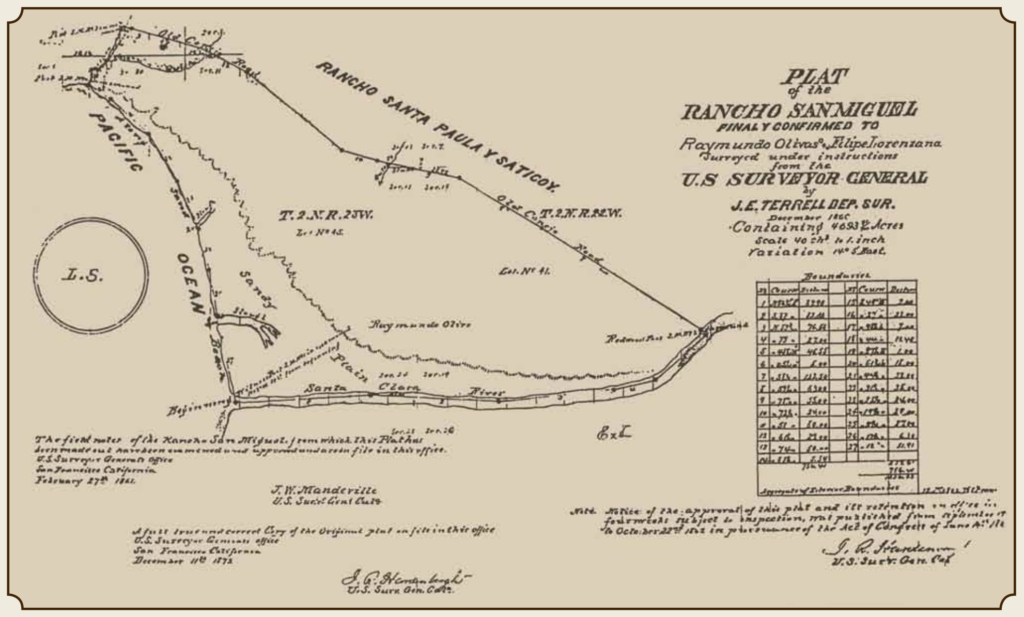

Raymundo Olivas and his partner Felipe Lorenzana received a land grant of around 4,700 acres in 1841 in return for their service in the Mexican Army, they named their land grant “Rancho San Miguel.” And soon after, Raymundo built a small one-room adobe house and moved in with his wife Teodora and began ranching his land—growing crops and raising cattle.

Photo Credit: The Olivas Adobe

Don Raymundo was successful enough that in 1847 he began construction on the first floor of the main house to accommodate his growing family—he and Teodora would end up having 21 children in total—8 girls and 13 boys.

The Gold Rush of 1849 was a boon for Don Raymundo, his cattle became his “gold mine” as he drove his cattle north to sell them for as much as $75 a head to meet the gold miners demand for food. Prior to the gold rush, cattle were worth around $2.50 a head for their hides and tallow. With his new income, Don Raymundo added a 2nd floor to the main house, with much of the work done by Chumash Native American workers, who were skilled in adobe making and construction. The 2nd floor was completed sometime between 1850 and 1852.

In the 1860s a drought decimated the cattle industry in California, but Don Raymundo was able to survive by raising sheep instead and making another fortune in wool.

His partner Felipe didn’t fare as well, he ended up selling his half of the rancho, leaving Don Raymundo with 2,500 acres on which to cultivate crops and raise livestock.

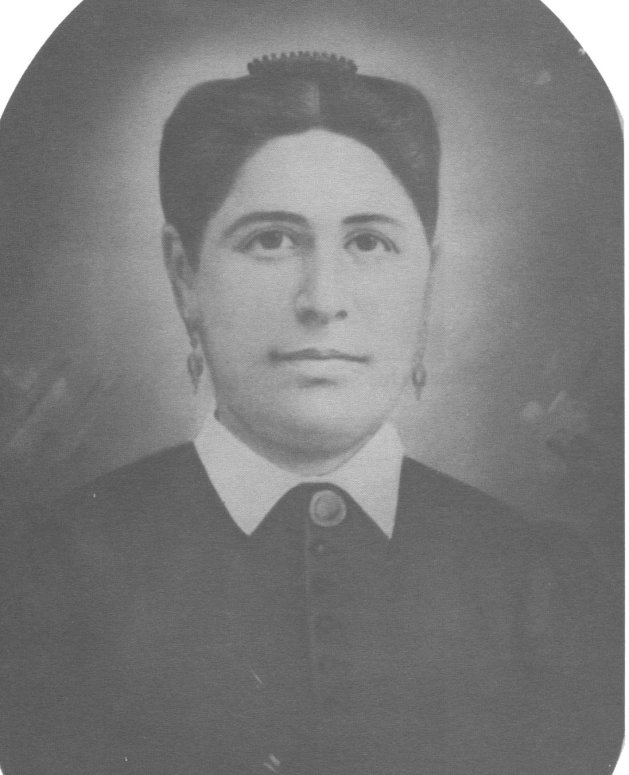

In 1879 Don Raymundo passed away and his death led to in-fighting amongst the family over his estate. His wife Teodora would pass away in 1895, leaving their youngest daughter Rebecca Olivas as the last member to live in the adobe until it was sold in 1899 along with the surrounding property.

Photo Credit: The Olivas Adobe

The adobe passed through a series of owners until it was purchased in 1927 by Max Fleischmann, who restored the building and used it as a hunting lodge for duck hunting. Fleischmann passed away in 1951 and his estate gifted the adobe and funds for restoration to the city of Ventura in 1963 and it opened to the public in 1972.

Today you can take a tour with a docent dressed as Doña Teodora and see some of the items owned by the Olivas, like this ornate music box.

So, what type of legends and ghost stories are told about the adobe?

One legend says that in the 1850s a group of bandits robbed the rancho and stole thousands of dollars’ worth of gold and even they ripped the earrings out of Doña Teodora’s ear lobes. The bandits were later caught and hanged, but the gold was never recovered. It’s rumored that they buried the bags of gold somewhere in a nearby mountain. It’s said that the spirit of one of the bandits guards the treasure and that

a few of those who have gone in search of the treasure never came back alive.

The adobe is said to be haunted by a few ghosts—a ghost dog has been seen and heard barking on the property and phantom bride is said to appear in the chapel, but the 2 most famous ghosts are Maria and The Lady in Black.

Maria is said to be around 7 or 8 years old and has been seen in few rooms around the house. According to one source, records do indicate that a Maria Olivas did pass away in the house. It’s said that if you call out her name, she will appear.

The most famous ghost of the adobe is the lady in black. She’s been reportedly sighted since the house opened as a museum in 1972. Some groundskeepers saw her looking out from one of the 2nd floor windows. Thinking that someone had broken into the house, they called the police, but when they got there and checked they didn’t find anyone. She’s been sighted a few times and is described as wearing an old fashioned, long sleeve black dress with her hair up in a bun. The museum even has a picture of a wedding that took place at the adobe that has a mysterious figure watching over the celebration from a doorway on the 2nd floor. Some say that she’s Doña Teodora, who passed away in the house. While others say she’s Dominga Olivas, the wife of their son Raimundo Jr. who died in childbirth in 1894. Whoever she is, apparently her spirit is not at rest.

Photo Credit: The Olivas Adobe

So, the next time you’re in Ventura, make sure to pay a visit to the Olivas Adobe and check out this outstanding example of a two-story adobe house. And who knows, you just might run into the previous owners.

Our next stop is the Leonis Adobe here in Calabasas. This is the oldest surviving private residences in the San Fernando Valley and it’s said that its past residents are still making their presence known today.

Photo Credit: The Leonis Adobe

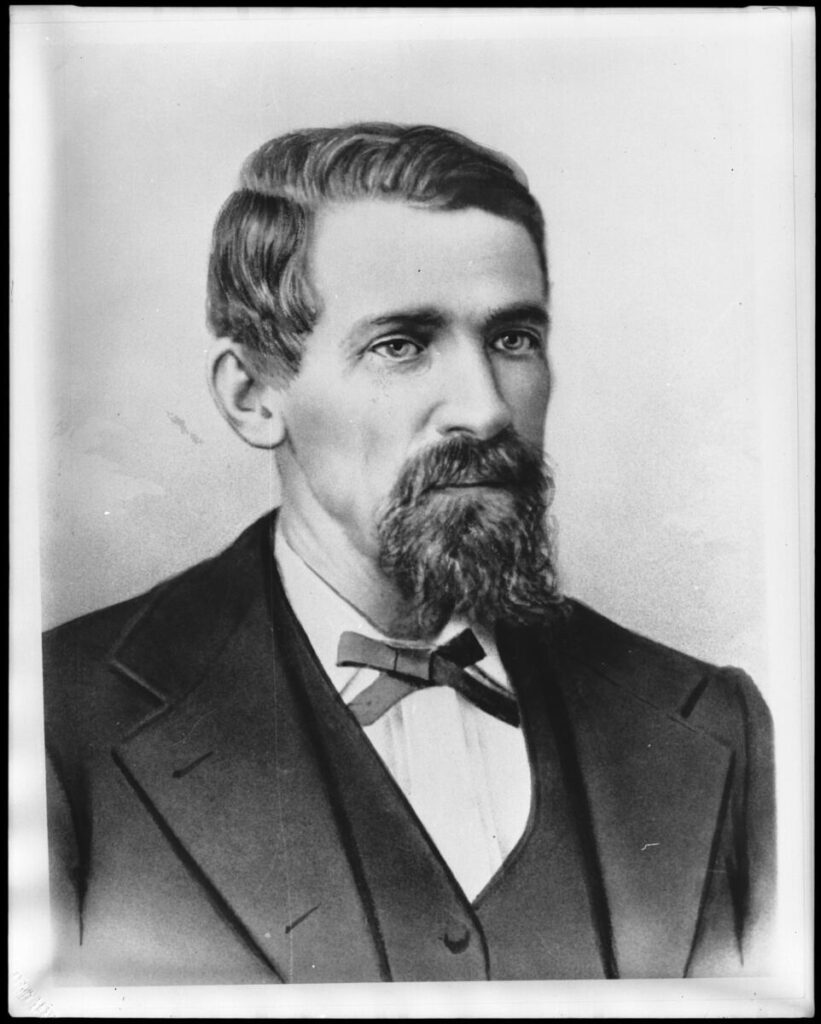

Miguel Leonis was a French Basque immigrant, who was illiterate and spoke no English or Spanish, but managed to amass a ranch that encompassed most of the Western San Fernando Valley and part of Ventura County. He arrived in Southern California in 1858 and went to work as a sheepherder for Joaquin Romero, who owned half of Rancho El Escorpion. Shortly after being hired, Leonis was made “mayordomo” of the ranch and soon took over the entire operation from Romero. He eventually persuaded Romero to sell him his half of Rancho, including his livestock for $100.

Photo Credit: USC Libraries and California Historical Society

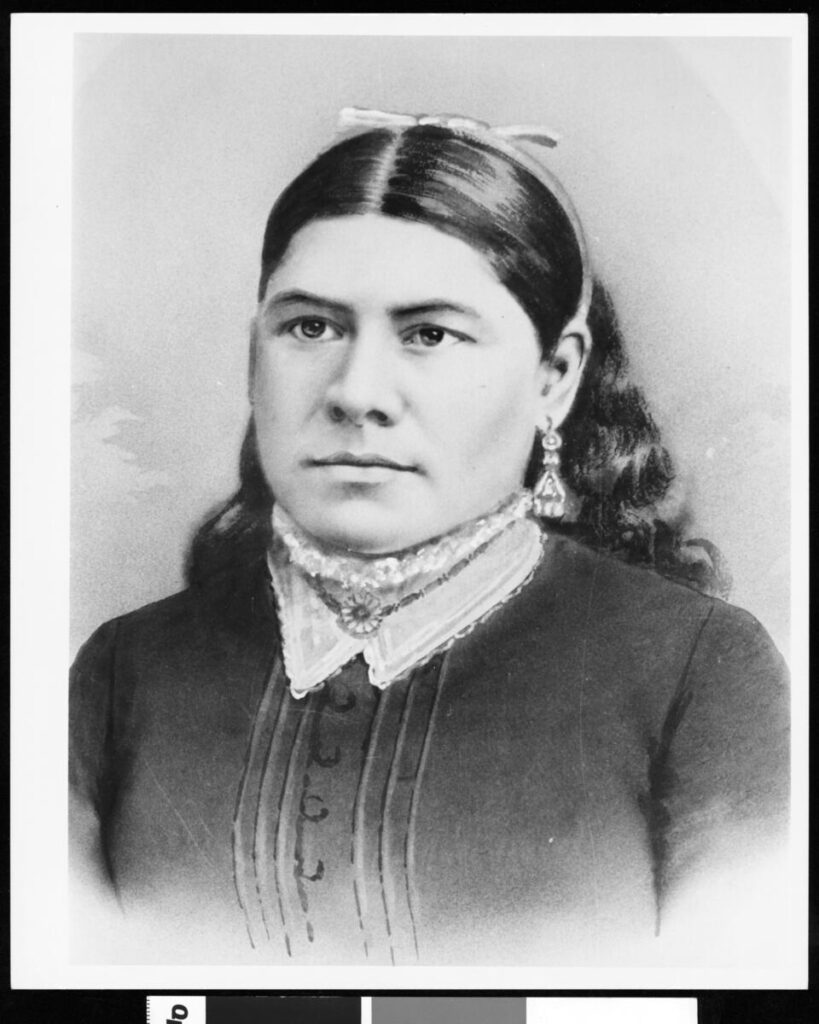

Under Leonis, the rancho prospered and driven by his ambition, he turned his attention into to acquiring the other half of Rancho El Escorpion. He began a relationship with Espiritu Chijulla, a widow of Chumash and Tongva descent, whose father owned the other half of the rancho along with two of his relatives. Through this relationship, Leonis was able to acquire the entirety of the rancho.

Leonis and Espiritu soon moved into an old, abandoned adobe that Leonis restored and made his place of residence, which would become known as the Leonis Adobe.

Photo Credit: USC Libraries and California Historical Society

Leonis continued his aggressive expansion of his land holdings, taking advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862, that allowed anyone to claim unappropriated land if they established residency and made improvements to the land. By this time, Leonis had around 100 employees, so wherever his livestock grazed, he would build a crude shack, have one of his employees live there, and then file a claim on the land. This is how he amassed thousands of acres of land and gained the nickname of the “King of Calabasas,” and he certainly ruled over his land like tyrannical king. He fiercely defended his land from squatters, dispatching his mounted and armed men to intimidate and drive them out, sometimes at the cost of the squatter’s life.

In 1899 while driving back through the Cahuenga Pass heading home with a few of his workers, Leonis fell from his wagon and was crushed beneath its wheels. Gravely injured, he was taken back to the adobe where he passed away 3 days later. At the time of his death, his estate was valued at $300,000 and he owned over 10,000 acres of land. In his will, he only left $10,000 to Espiritu, referring to her as his housekeeper and not his wife, despite having lived together for 30 years and having a daughter together, who had tragically passed away at age 20. He instead left the bulk of his fortune to his siblings back in France.

Espiritu took the highly unusual step to challenge the will and sue for a wife’s share. After a 16-year battle, she won her case but passed away 7 months later. Her son Juan from her first marriage continued to live in the adobe with his family until he sold it in 1922 to the Aguore family, who made many improvements to the adobe and property. After the Agoures lost the property due to foreclosure in 1931, the adobe passed through many owners and uses, it was once a chicken restaurant and was also used as a retirement home, before it fell into a state of neglect.

Despite being designated as the first Historical Cultural Monument in the city by the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board, in 1963 the adobe was slated to be demolished to make way for a shopping center. Luckily Mrs. Kathleen Beachy stepped in to lead an effort to purchase the property for historical preservation and in 1963 she bought the adobe and 5 surrounding acres.

Mrs. Kathleen Beachy receiving an honor from the city for her preservation efforts in the Los Angeles Times Sept. 24, 1964

Renovations began in 1965, and the adobe opened to the public as a museum in 1975. Today the adobe is a living museum dedicated to preserving and sharing 1880s ranch life—you can even feed animals that would’ve been raised on a typical rancho in the 1880s.

So, what type of ghost stories are told about this adobe?

Right after the Agoures moved in, they heard footsteps on the upper floor followed by the sound of thuds, as if boots were being removed. When they went upstairs to investigate, they noticed the distinct scent of soap, an aroma that is associated with Leonis, who is said to have always appeared impeccably clean and smelled of soap. The ghost of Leonis has also been reportedly see. A house docent and two companions saw the shadow of a very tall man suddenly appear on the living room door and quickly disappear. Leonis was 6 foot 4, so they were convinced that this was none other than the spirit of Leonis.

Espiritu has also been reportedly seen and heard—a ghostly figure was seen in the hallway and heard whispering, “Chichita, Chichita,” which was Espiritu’s nickname for her granddaughter.

So, if you’re ever in Calabasas, make sure to swing by the Leonis Adobe to learn about rancho life in the 1880s and the life of Miguel Leonis and Espiritu, and if listen closely, you just might hear them too.

Our next and final stop is Agua Mansa Cemetery in the city of Colton. This cemetery is all that remains of the communities of La Placita and Agua Mansa, and like most cemeteries, it’s rumored to have a few restless spirits.

In the 1830s Antonio Maria Lugo and Juan Bandini established the San Bernardino and Jurupa Ranchos on land that formerly belonged to Mission San Gabriel. They convinced a group from Abiquiu, New Mexico led by Santiago Martinez and Manuel Lorenzo Trujillo, to settle along the Upper Santa Ana River by offering them land with the understating that the new settlers would serve as a buffer against raiders and outlaws along the trading route from Santa Fe to Los Angeles.

After first settling in Politana on the Rancho San Bernardino in 1842, Trujillo moved some of the group to a 2,000 acre plot on the east side of the river and established a village that was known as “La Placita de los Trujillos.” A second group led by Martinez moved to the west side of the river and established another village called “Agua Mansa,” which means “gentle water” in Spanish. This was an ironic foreshadowing of a disaster to come.

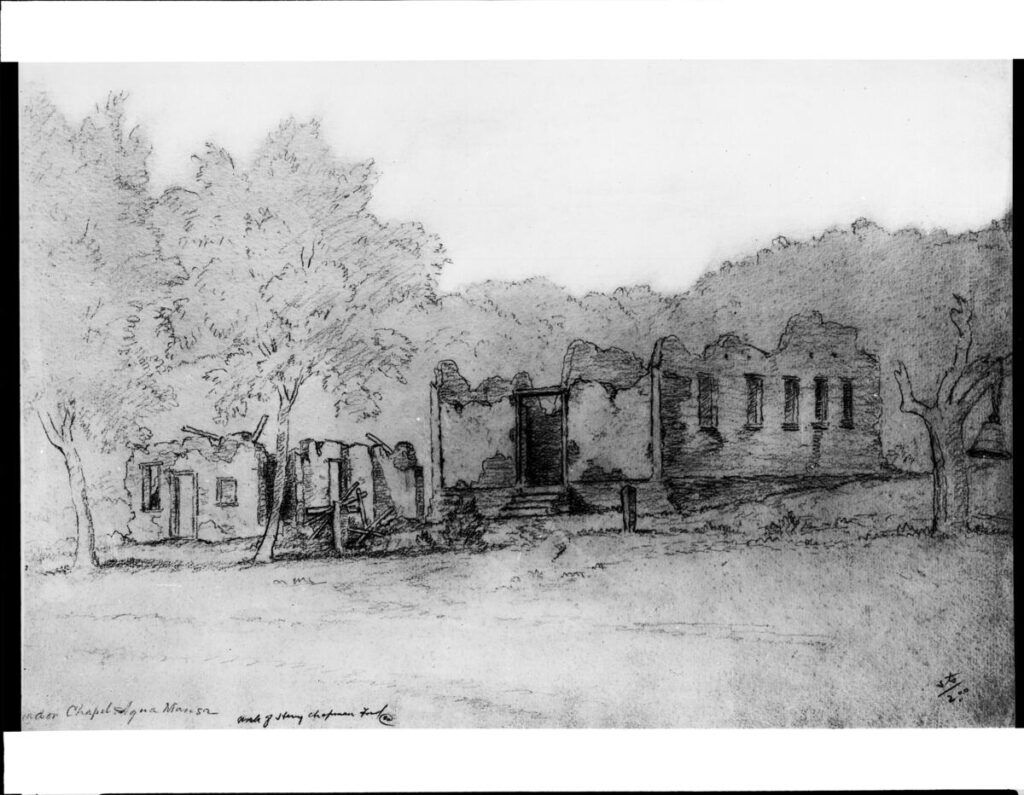

By 1845, both communities were well-established, with farmsteads set up, a large irrigation system constructed, and crops such as grapes, grains, vegetables, and fruit trees planted. Their horses, sheep, and cattle grazed on the southeastern mesa, in present-day Riverside. A church that was built in La Placita collapsed almost immediately after it was completed in 1852, so another chapel was built in Agua Mansa in 1853 and dedicated in 1857 as “San Salvador.” The cemetery was also established in Agua Mansa near the chapel. The two communities flourished until 1862, when a great flood decimated them, sweeping away most of the adobe buildings. Luckily, no lives were lost, but only a store, the chapel, and the cemetery survived the storm.

The 2 communities were rebuilt, but they never regained their importance—the coming of the railroad, the start of the cement industry, and the expansion of the citrus industry drew people away from the communities, eventually leading them to all but disappear, save for the cemetery.

While the last burial at the cemetery took place in 1963, in the years prior, the graveyard had fallen into disrepair and had become overgrown and vandalized. In 1955 a descendant of two of the original families formed the group “Friends for the Preservation of the Agua Mansa Pioneer Cemetery” to fence-off and refurbish the cemetery. In 1967 San Bernardino County took over administration of the property and in 1978 a full-size replica of the San Salvador Chapel was built to serve as a museum. The grounds recently underwent a major refurbishment which included a new entrance gate, new drive, landscaping, new interpretive signage, and the preservation of some tombstones.

Today you can visit Agua Mansa and learn about the settlements and the people who lived and died there. You can also stroll through the cemetery grounds and see the final resting place of many prominent families from the Inland Empire, including Trujillo, Rubidoux, Jensen, and Alvarado.

So, what type of ghost stories are told about the cemetery?

There are various reports of paranormal activity, including apparitions, but there are 2 stories stand out.

The first is a spectre that’s been seen walking his dog on the road that goes right by the cemetery.

But the most famous ghost is that of the legendary La Llorona, who is said to roam the cemetery and the nearby banks of the Santa Ana River in search of her drowned children.

So if you’re ever in the city Colton, make sure to pay a visit to Agua Mansa cemetery and learn about some of earliest non-native settlers of the Inland Empire. Just make sure to do it during day, there’s no telling who or what you might hear once the sun goes down.