I was recently on the “I’m Being Seriously” Podcast where host Alexis Chavez asked if we could talk about Highland Park History. I did a lot of research on different historic spots in that neighborhood that I decided to make a video on 3 of my favorite spots.

The first stop on my list is Chicken Boy, probably one of the most unique landmarks in Highland Park. This half-chicken, half-human statue holding a bucket of chicken certainly has a history as interesting as his appearance.

The Chicken Boy Fried Chicken Restaurant was opened in 1969 on Broadway, between 4th and 5th streets in downtown L.A. The restaurant decided that they needed something eye-catching to draw in customers, so they bought a statue from International Fiberglass Company of Venice, who manufactured roadside Paul Bunyan and Muffler Man statues for outdoor advertising. They had an artist customize the statue—having a chicken head replace the man’s head and having the arms modified to hold a bucket of chicken instead of an axe.

In the early 1970s, Amy Inouye came to Los Angeles to attend the L.A. Center of College and Design. One day while heading to the Grand Central Market, she spotted Chicken Boy and instantly felt a connection to the statue—it became her symbol of the city. She even called it the “Statue of Liberty of Los Angeles.” She would drive by often, on her own or to show him off to out of town visitors.

One day in 1984 She saw a “for lease” sign on the restaurant and her heart sank. What would happen to Chicken Boy? She called the leasing agent repeatedly until they basically told her, “if you want him, come and get him.”

She spent the next several days trying to find someone to help her move and dismantle the 22 foot statue and put him in storage. She had saved Chicken Boy, but needed to find a new home for him.

She was sure that he would be welcomed at one of the various L.A. art institutions, but nobody was interested in taking in Chicken Boy.

One year as a holiday gift to clients, Amy re-created t-shirts that had been sold at the restaurant, the next year she made lapel pins, then watches. She then made a souvenir catalog in 1987 that included several Chicken Boy items—the catalog went viral before that was a thing and helped her pay for his storage—at one point she had 14,000 people on the catalog’s mailing list. Chicken Boy even had a movie made about him in 1991 and had a “Chicken Boy Day” declared in 1993. But still, she couldn’t find a place to display him.

You can see “Chicken Boy: The Movie” below:

Then in 1994 local radio station KZLA covered Chicken Boy’s story and many listeners reached out— The Arco Plaza donated some space to display him and several businesses helped in his restoration—and for the first time since he left his roost on top of the restaurant, Chicken Boy was whole again. He was on display for several weeks, before the mall requested, he be taken down and back into storage he went.

Despite having several offers from different businesses to purchase Chicken Boy, Amy was determined that he stay in L.A. and be put back on a roof someday. She found that space in Highland Park in 2007 and she was able to get a grant to install him on the roof of her gallery—Chicken Boy had found a new place to roost.

Today he is one of Highland Park’s most unique landmarks, catching the attention of drivers as they drive up Figueroa, much like he did when his roost was in Downtown L.A.

The next stop on my list is Galco’s Soda Pop Stop, a neighborhood Italian grocery and deli that became a soda lover’s paradise.

Galco’s can trace its origin back to 1897 when the business began as a small Italian grocery store near the present-day intersection of Vermont Avenue and Pico Blvd. The name Galco’s comes from combining the first few letters of the 2 founders last names, Galioto and Cortopassi.

They moved the store shortly after to Chinatown and in 1940 Louis Nese became a partner in the grocery store and eventually took over the business and moved it to Highland Park in 1955 and continued to operate it as an Italian grocery store and deli.

In the 1990s sales at Galco’s were dipping as larger chain stores took over distribution channels and prices for small groceries, including soda, went through the roof. John Nese, the second-generation owner, decided that in order to protest against the large soda companies not offering the same price as his larger competitors, he was going to stock his shelves with smaller brands of soda from independent bottlers. His bet paid off and soon Galco’s was the go-to spot for people to find sodas from their childhood or try something new.

Business really took off after Huell Howser visited in 2000, the store went from having 2 aisles dedicated to around 250 sodas to overhauling the whole business and switching to strictly beverages that now includes over 700 different sodas and a variety of beers, and other alcoholic drinks. They also stock a wide variety of old-fashioned candies. And you can even make your own soda.

One thing that’s remained constant is the deli part of the store which still serves up their famous “Blockbusters” that got their name from boxing legend Rocky Marciano who grabbed a sandwich during one of his visits to L.A. and said, “wow, this is a real blockbuster!”

Galco’s continues to flourish today thanks to their willingness to take risks and I hope they continue to thrive for many generations to come.

The last stop on my list is a house that is as unique as its owner was, “El Alisal” or The Lummis House.

Charles Fletcher Lummis was certainly an interesting character. He dropped out of Harvard to become a poet, then while working for a newspaper in Cincinnati, he was offered a post with The Los Angeles Times and decided to walk to his new job. He walked over 3,500 miles in 143 days, sending weekly dispatches to the newspaper. It was during this trip that he became enamored with the American Southwest, which would influence much of his life’s work.

He arrived in Los Angeles in 1885 and was made City Editor of the Times. It was one of many jobs that he would have during his life, including city librarian, ethnographer, and museum founder among others.

In the late 1890s he bought 3 acres along the Arroyo Seco that he named “El Alisal” or “The Sycamore” after a grove of sycamores that were on the property. He built a small cabin on the land for his family to live in while he worked on building the main house.

As I said before, Lummis was an interesting character and he felt that his house should reflect his personality.

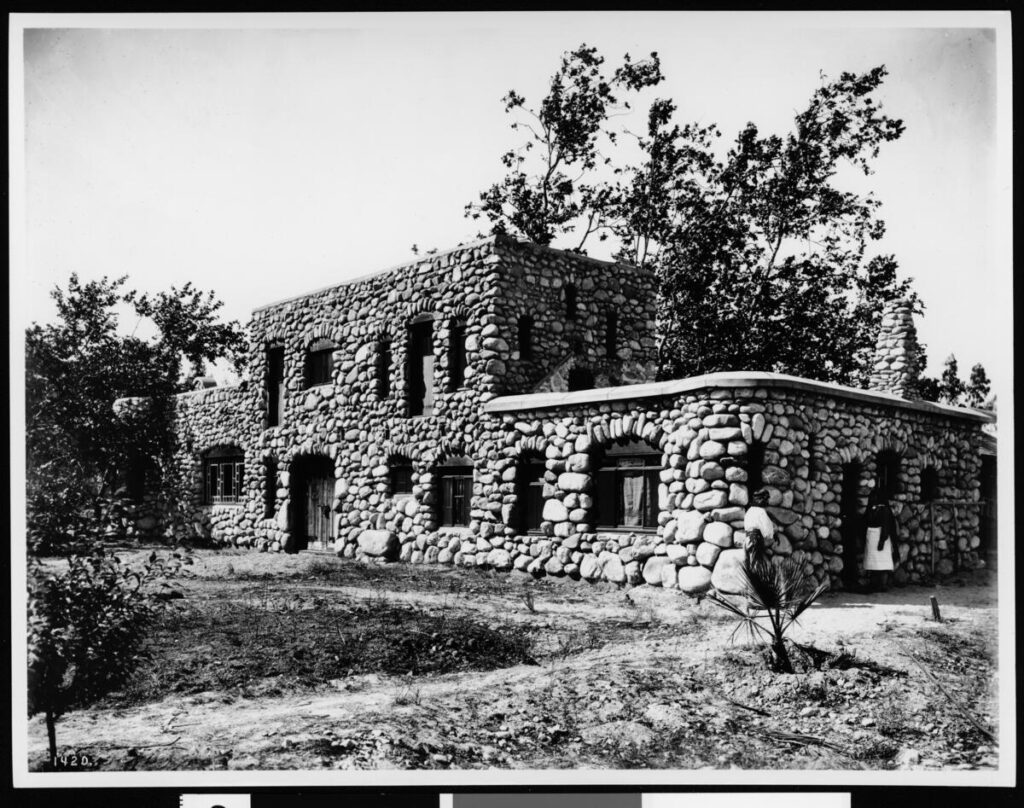

He spent about a decade and a half building his home, using boulders from the nearby Arroyo Seco, cement, and even telephone poles. He was assisted in the construction by Pueblo Native Americans that he had befriended on his trips through the Southwest.

Photo Credit: USC Libraries and California Historical Society.

The house is an 18 room Spanish-Colonial castle that reflects who Lummis was;

The floors are made of concrete in order to make them easier to clean, he was notorious for throwing all-night parties that he called “noises,” the house has some low doorways due to Lummis’ short stature, and details around the house reflect his interest in the American Southwest, especially Native American culture. His passion for Native American culture led him to found the Southwest Museum in 1907, which was the first museum in the city.

Photo Credit: USC Libraries and California Historical Society

Lummis passed away in his house in 1928 and his ashes were interred in a vault in one of the walls. His house was deeded to the Southwest Museum, then sold to the state of California in the 1940s and then transferred to the city of Los Angeles in the 1970s.

Today, the house is maintained by the city’s Department of Recreation and Parks as a museum and they maintain the grounds and garden of native plants.

The Lummis House is not only a unique testament to its unique owner, but is also a welcomed oasis from the hustle and bustle of the city.

References:

“The True Story of Chicken Boy” by Amy Inouye.

“Only in L.A.” by Steve Harvey, The L.A. Times. Aug. 16, 1991.

“Chicken Boy, Once and Future Ruler of the Roost” by Al Martinez, The L.A. Times. March 19, 2007.

Galco’s Soda Pop Stop | L.A. Conservancy

“It’s a Marriage with Remarkable Shelf Life” by George Ramos, The L.A. Times, Jan. 29, 2003.

Visiting with Huell Howser: Galco’s

“No. 129: The Lummis House/ ‘El Alisal’” by Etan Rosenbloom

Southwest Museum | L.A. Conservancy

“Facts and Figures: Lummis House” by Friends of Residential Treasures:LA”